Our increasing morbid fascination with true crime and serial killers has been a widely controversial topic for a long time. It is a positive in the sense of becoming more aware of how to keep ourselves safe, but also a negative, since many of these killers end up gaining a twisted celebrity status that overshadows the people who are affected by their crimes. While Criminal Minds feeds our voyeuristic and slightly sadistic need to consume grotesque media by creating elaborate and disturbing ways to kill a person, it also subtly works to de-glorify serial killers in an unexpected yet powerful way. As we delve into the twisted depths of the mind of a serial killer, through the BAU’s (Behavioral Analysis Unit) technique of criminal profiling, we find rather human emotions and trauma lurking at the bottom. Being able to identify with some of the emotions the childhood version of the killer feels, humanizes them while also stripping them of their power. Subsequently, Criminal Minds turns the serial killer and victim dichotomy into the mere atrocious act of one human killing another.

‘Criminal Minds’ Uses Profiling To Deglamorize Serial Killers

Like most cop procedural dramas, Criminal Minds uses an episodic structure detailing one crime in each installment while having an overarching gimmick in its premise. Criminal Minds’ gimmick is not only specifically focusing on serial killers but also using psychoanalytical tools, or criminal profiling, to gain deeper insight into the killers’ behaviors and motivations, allowing for their arrest. This gimmick becomes key in stripping the serial killers of their power and romanticization. A serial killer’s MO (modus operandi – method of killing) and their signature tend to be what makes them unique and becomes the source of their fame. As such, through the BAU’s profiling, their sickening and glorified actions are slowly deconstructed from otherworldly and a source of fascination, to quite mundane.

At the crux of each serial killer tends to be a range of emotions that are actually quite relatable, like rage, guilt, or envy. These simply become so twisted that they become unrecognizable to an everyday person, becoming wrought enough for the person to begin killing. As such, by reducing the killer into something we can identify with, Criminal Minds destabilizes the pedestal that held them up and thus promptly strips away their power. As the profilers systematically tick off a checklist of triggers, childhood traumas, and personality traits, they whittle down the killer until they become a shell of what they were in the grandeur of their opening scene in the episode.

Showcasing serial killers in this impersonal light has been another source of controversy, as seen in Zac Efron’s portrayal of Ted Bundy in Extremely Wicked, Shockingly Evil and Vile. Many viewers were displeased with how charismatic and seemingly normal Bundy was portrayed as in the Netflix film, though many reports have confirmed that Bundy was in fact all these things. Criminal Minds also has examples of charismatic killers like Benjamin Cyrus (Luke Perry), a cult leader who married and sexually assaulted underage girls, and prepared a mass suicide introduced in Season 4, Episode 3, “Minimal Loss.” Yet, the show’s exploration into his childhood, where he was abandoned and rejected, makes his grand motivations seem like petty revenge, reducing him to yet another despicable human.

Henry Grace Is Not the Genius We Thought in ‘Criminal Minds’

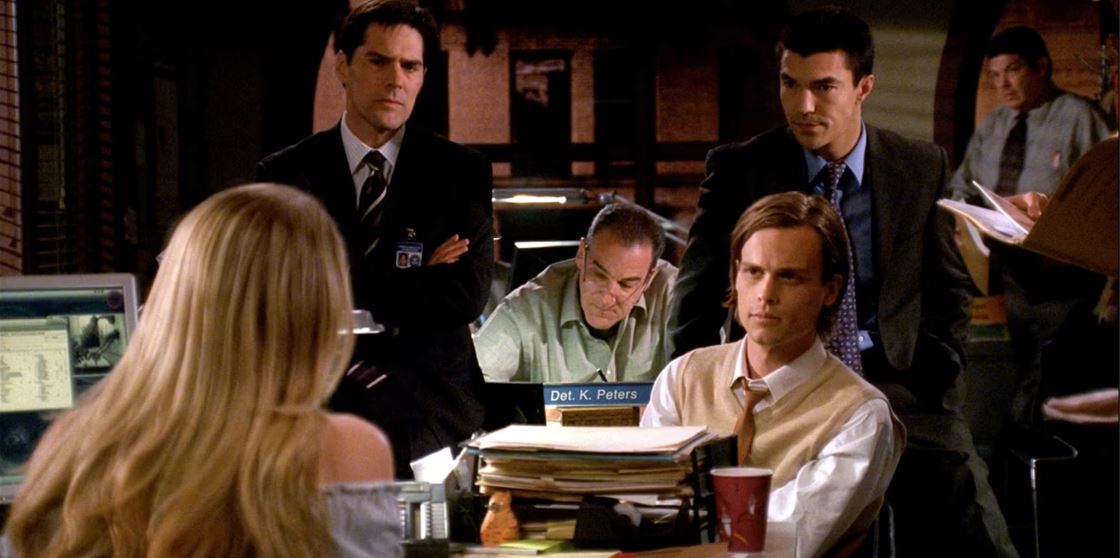

The most jarring example of this deconstruction is in Season 4, Episode 8, “Masterpiece,” where the serial killer’s use of the golden ratio, pursuit of perfection, and status as a genius is often hailed as one of the more terrifying and creepy serial killers in the show. This episode departs from the usual structure of the show, as Henry Grace (Jason Alexander) is introduced fairly early into the episode and actually reveals his ominous plans to Spencer Reid (Matthew Gray Gubler) and David Rossi (Joe Mantegna). His chilling entrance is enhanced by Alexander’s creepy portrayal of the character, with his peaceful voice and unwavering stare. He lays out a game for the FBI, encouraging them to find his latest victims, who are trapped in a solid steel container with a video feed streaming to the FBI. Grace’s entire introduction lends to serial killers vying for notoriety, wanting his genius and gall to earn himself a place among the podium of serial killers society has glamorized.

As the team investigates Grace’s MO further, the mastermind and artistic aspect of his crimes are revealed, further romanticizing his work in an unsettling way. We discover that he is adhering to the golden ratio, often referred to as the mathematical symbol for perfection, as he abducts and kills women. The golden ratio is signified by the Fibonacci sequence, where the next number in the sequence is the sum of the previous two, and when graphed, it creates the revered spiral shape. Grace was also using the Fibonacci sequence to determine the number of victims in each bout of killings (1, 1, 2, 3 …), and in this episode, he was up to 5. By the end of the episode, we learn that the abducted women and children in the stream were not the real victims – the 5 FBI agents that raid the house would be. All these revelations further propel Grace’s mythical genius status, seemingly adding to the romanticization of serial killers.

However, he is effectively checkmated by Rossi, who puts his perceived arrogance aside and discerns the true motives of this killer. Turns out, Grace had pushed this plan into motion as a plot for revenge against Rossi, who had convicted his brother and led him to the death penalty. In one fell swoop, Criminal Minds’ quick deconstruction of Grace’s grandiose pursuit of twisted perfection renders this strange indescribable figure into a more pathetic and desperate human. With almost cheap motives of revenge, Grace becomes more recognizable. It also makes his efforts to use these gimmicky signatures and MOs just plain convoluted and pitiful, effectively stripping him of his power and mystique.

How Does ‘Criminal Minds’ Put the Victims First?

In efforts to condemn serial killers, media like documentaries and fictional representations of true crime have been trying to shift the focus away from the killers and onto the victims. Though the bulk of most Criminal Minds episodes are about deconstructing the killer, they sensitively handle the topic of the victims in subtle ways that actually become quite powerful.

While, every now and then, the show will have a victim-centric episode that zones in on their experience, most of the time we will hear about them through a crucial step in their profiling technique: victimology. As Aaron Hotchner (Thomas Gibson) regularly emphasizes, victimology is an integral part of assessing a killer’s behavior and mindset. However, this also means that the victims are almost always the first thing they talk about, deftly ensuring that viewers understand that these are real humans and lives that have been stolen. Though they list off the victims’ occupations, interactions and physical features in an organized, impartial manner, there are always quick comments on the horror of the loss of life, or how the victims’ family would feel, or even occasional outbursts of reminding themselves to remain objective, so they can bring justice to the victims and the families.

This humanization of the victims is also helped along by the team’s treatment of the killer. As soon as a case is showcased in the meeting room, the killer is given the title of the “unsub” – unknown subject. This more scientific and objective description somewhat lends to reducing the killer’s power, but it more importantly keeps the killer at the same level as the victims.

They are both analyzed in a measured way, so even though the killer is naturally spoken about more, they aren’t necessarily given preferential treatment, nor are they idolized. This is also accentuated by the unit’s overt disapproval of giving a serial killer a catchy epithet that promotes a larger-than-life persona and detracts from the victims. Hotchner also indicates the dangers of naming a serial killer in Season 4, Episode 6, “Catching Out,” where The Highway 99 Killer’s name distracted the cops from realizing the unsub was actually using trains to move around, providing another way of how idolizing serial killers can impede the path towards justice for the victims. As such, despite the series’ primary focus on the killers themselves, they effectively ensure the victims are humanized and the loss of a beloved human life is recognized in subtle ways.

‘Criminal Mind’ Humanizes Serial Killers Effectively

Criminal Minds not only humanizes the victims but also the serial killers, a decision that has sometimes proved to be controversial. Netflix’s Dahmer – Monster: The Jeffrey Dahmer Story is a prime example of this, as serial killer Jeffrey Dahmer was almost painted as a sympathetic figure, then his later actions were framed in a glorified way. Rita Isbell, sister of Errol Lindsey who was murdered by Dahmer, tells Business Insider how she was never informed about her life and traumatic experience being cast in the Netflix show, feeling like her pain and her brother’s death were being monetized. As such, Criminal Minds’ choice to humanize the killer can become a point of contention, but, the outcomes of them doing so actually end up de-glamorizing them.

While the team deconstructs the unsub into childhood traumas and personality traits, they also humanize them, accentuating the fact that it is a human that committed these crimes against other humans. Although there are definitely unsubs we sympathize with more than others, like in Season 5’s “The Uncanny Valley” where an abused woman kills other women to replace her doll collection, it emphasizes how ghastly their actions are. It also alludes to “situational evil,” as demonstrated i