In the end, Ethan Edwards can’t go home again. The central figure of The Searchers, director John Ford’s epic Western, spends most of the movie’s runtime as a murderous, racist bastard. Though Ethan eventually does save the day and rescues his abducted “niece,” Debbie, domestic bliss will forever elude him. In the final shot of the movie, he watches as his family enters their cabin to live happily ever after. Ethan, however, cannot join them, forever damned to the Hell of the Old West.

More than 60 years after its original release, The Searchers lands on just about every list of The Greatest Movies Ever Made. Released in 1956, the movie adapts the novel of the same name by Alan Le May. Ford, the director most closely associated with the classic Western, helms the film from a script by Frank S. Nugent. The movie even stars the most iconic actor to appear in Westerns, John Wayne. Yet, for all the talent on display, for all the power and majesty of the film’s vistas and performances, The Searchers doesn’t enjoy the same perennial cult status as other films of the era, such as Singin’ in the Rain or Sunset Blvd. The reason? Ford demystified the West into a disturbing, bitter pill that will leave audiences conflicted and melancholy. Yet, it’s this very same contradiction that makes the movie the greatest Western ever filmed.

The Searchers Chronicles Obsession & Kidnapping

The Movie Was a Darker Spin on Classic Cowboy Stories

The Searchers begins in 1868. Former Confederate soldier and hero of the Second Franco–Mexican War Ethan Edwards (Wayne) returns to the home of his brother, looking forward to his retirement. He dotes on his nieces and nephews, in particular 8-year-old Debbie, who hadn’t even been born when he left for war. Ethan shows affection to all but one member of the family: teenage Marty Pawley (Jeffrey Hunter), whom Ethan’s brother adopted. Marty has blood relation to Ethan and his family, but Ethan rejects him for his mixed race. Having Comanche lineage disqualifies Marty in Ethan’s mind, not just as a family member, but as a member of the human race.

While Ethan and Marty venture out investigating cattle thieves, a Comanche raid destroys the Edwards homestead. The pair return to the ranch to discover Marty’s brother and father murdered, and his adoptive mother violated and killed as well. Despondent, the pair also find evidence that the raiders took Ethan’s two nieces, Debbie and Lucy, as captives. Ethan and Marty then begin a five-year journey tracking the Comanche chief Scar (Henry Brandon), in hopes of saving Debbie and Lucy.

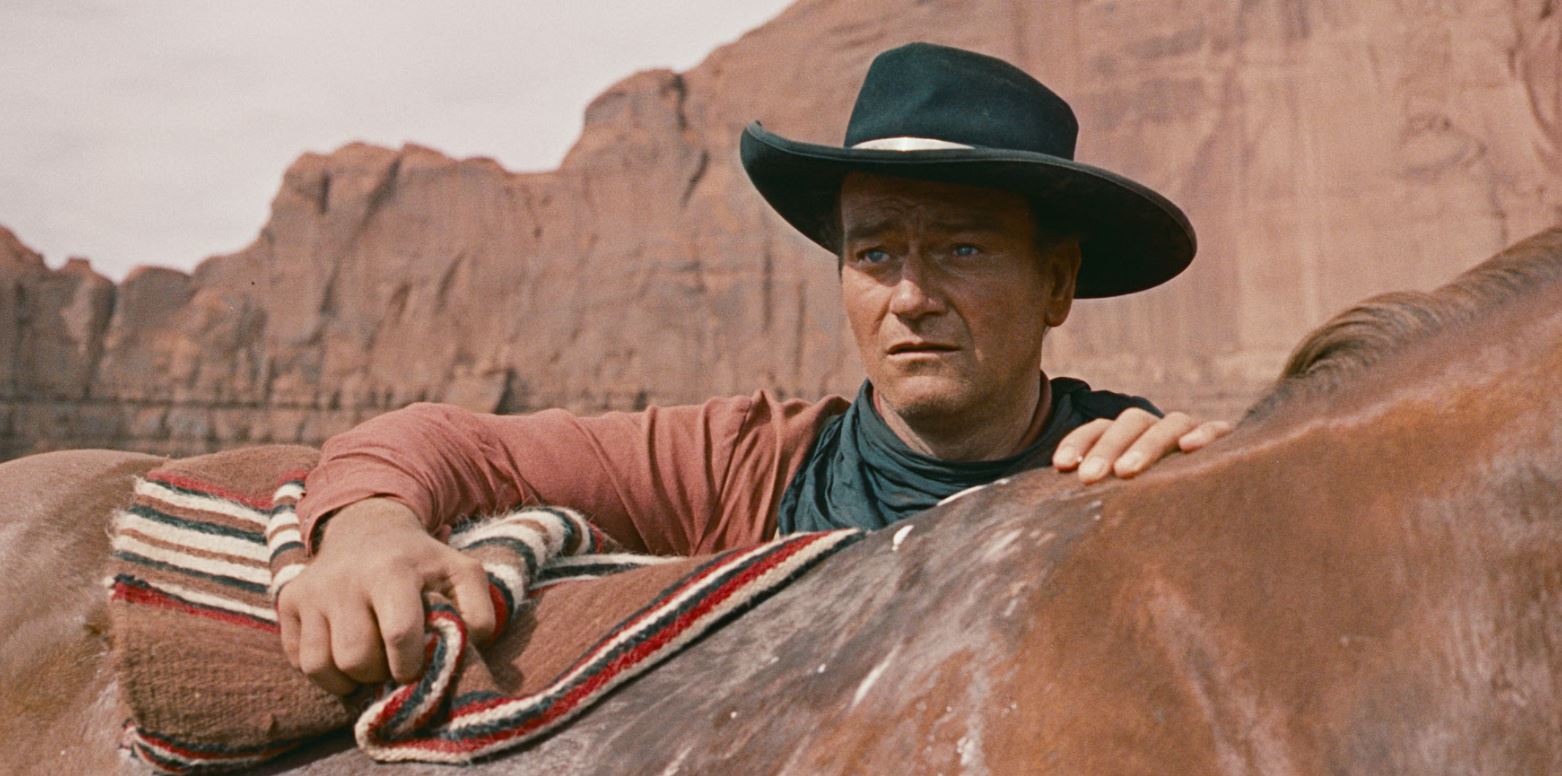

Ford and Wayne made a staggering 14 films together over the course of their careers, almost all of them Westerns. Wayne always claimed that he owed his iconic status to Ford’s direction, not to mention his entire career as a leading man. In most of those movies, Ford cast Wayne as the archetypal Western hero: the cowboy with a heart of gold, defending the gentle, almost exclusively white, settlers from the perils of the frontier. Seeing Wayne, a paragon of Americana, play such a vile character here would have sent shockwaves through cinemas then and now. Through Ethan, Wayne reinterprets Wayne’s typically heroic archetype as a horrifying villain. Wayne, for his part, shows off a deeper range as an actor than ever before. His performance smashes the romantic cowboy image that he spent most of his career cultivating.

The Searchers Is a Blunt & Nuanced Depiction of the Wild West’s Darkness

The Movie Deliberately Destroys the Western Myth Its Creators Helped Foster

As a director, Ford also had a habit of romanticizing the West. One critic noted that his movies were “dripping with nostalgia.” In other words, the West, as presented by Ford, had a magical, idealized quality to it, almost like something from a fairy tale. Yes, the Old West had its dangers, but in most Ford movies, the land presented an opportunity for love, life and fortune to brave settlers. This was no longer the case with The Searchers. Here, Ford smashes his own myth. Though he again casts Wayne in a leading role, Ford eschews his usual presentation of the West as an idyllic, if perilous, world.

In The Searchers, Ford sees the West as a kind of Hell on Earth: the site of bloody race wars where women are the victims of sexual violence, where friends murder each other for money, and where men kill for sport. Ford crystallizes this deconstruction of the West in the casting Wayne as Ethan. By 1956, audiences recognized Wayne as a heroic cowboy. In The Searchers, they see their Hollywood hero rob a dead man, listen to him spout racist venom, and treat his own nephew like an animal. Most damning of all, it becomes clear throughout the movie’s runtime that while Marty wants to rescue his sisters and bring them home, Ethan wants to find them to kill them. After spending years with a Comanche tribe, in Ethan’s mind, the women will have surrendered their whiteness and given over to savagery. In his twisted worldview,killing them is the “civilized” thing to do.

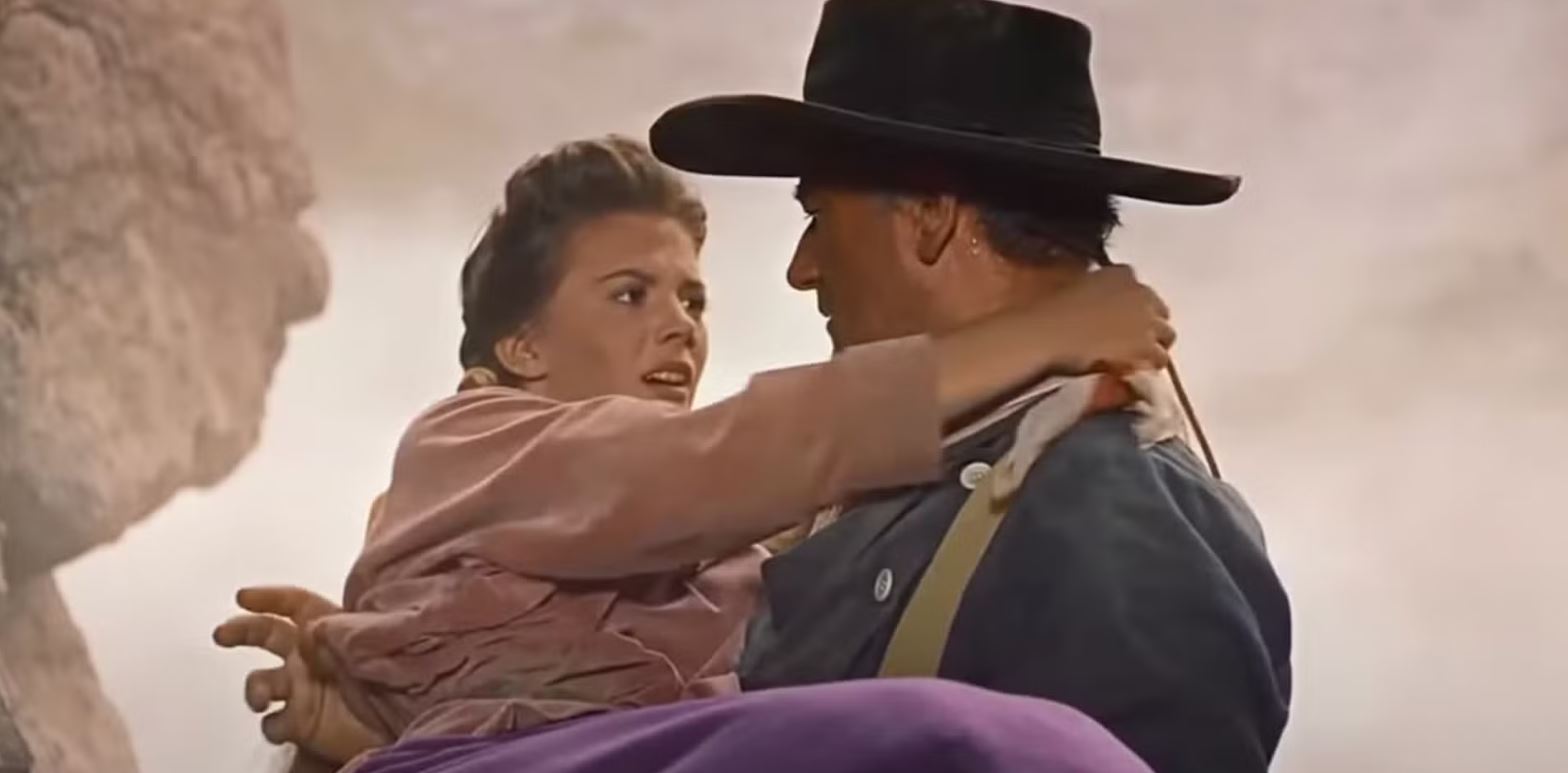

It would have amazed audiences in 1956 that Ford would demystify the genre he helped popularize, but even more amazing is the subtlety with which Ford makes his point. The Searchers contains no debates about racism, and no didactic speeches discussing the humanity of Native Americans or Latino settlers. Instead, Ford presents this world as is, and invites audiences to read between the lines. When Marty and Ethan finally locate Debbie (played as a teen by a young Natalie Wood), she doesn’t behave like an uncivilized animal. She recognizes the two of them, and weeps to go home. Ethan, however, ignores her pleas. He sees her as an aberration and tries to kill her on the spot. Marty, who previously lamented or recoiled at the thought of killing other men, stands his ground to protect her. He makes it clear he won’t hesitate to kill Ethan if he tries to harm Debbie.

The scene in question both spotlights Marty’s admirable growth and Ethan’s stagnant bigotry. For example, in a scene that comes early in the film, Marty and Ethan battle Comanche raiders. When Marty kills one, he doesn’t react with excitement. He buries his head in shame. Ethan, by contrast, relishes killing the Native Americans, suppressing a grin as he fires off his gun. A lesser film would have passed no judgment on Ethan’s bloodlust and would have portrayed the father-son dynamic between Ethan and Marty as a pure one. Marty’s trajectory would have ended with him “becoming a man” in the mold of Ethan, unafraid to kill. Ford subverts that expectation in The Searchers, with Marty growing into the anti-Ethan: a man unafraid to resort to violence to defend his family, and one who comes to see Ethan as the racist monster he is. Again, Ford accomplishes all this without any heavy-handed acknowledgment of what he’s doing. The director simply presents, and leaves the audience to observe.

The Searchers’ Female Characters Were Surprisingly Progressive for Their Time

The Movie’s Best Characters and Ideas Don’t Get Enough Praise and Recognition

On the subject of subtlety, Ford also makes two other powerful, if unspoken, points in The Searchers. Nobody would say the female characters in the movie pass the Bechdel Test; women in The Searchers appear as either the virginal daughter or the devoted wife. This isn’t much of a surprise, since these were the only roles women really got during the Western’s so-called golden age. And yet, Ford imbues these women with an intelligence and strength of character the men in the film seem to lack. Take, for example, Laurie, Marty’s longtime love interest. As played by Vera Miles, Laurie has the same grit and determination as her male counterparts. However, she also comes off as the most educated member of her family. Her parents rush to her side, asking her to read every letter delivered to the house. Laurie also shows a certain maturity that Marty doesn’t.

One memorable scene finds Laurie walking in on Marty in the bathtub. Whereas Marty rushes to cover himself in modesty, Laurie teases him, reminding him that because she has brothers, Marty doesn’t have any anatomy she doesn’t already know. Miles plays the scene both for laughs and as flirtation. She wants to see Marty naked, and has no shame for her sexual feelings. In an era of femal-centric sex comedies like Bridesmaids, Laurie’s libido may seem tame. But in 1956, showing a teenage girl with any kind of lust went against the norm. This would have either amused or shocked audiences; there is no in-between.

Meanwhile, Dorothy Jordan plays Martha Edwards, Ethan’s sister-in-law. Keen-eyed viewers have long picked up on another key, unspoken plot point in The Searchers. Observe the yearning in Martha’s eyes when Ethan returns home after the war. Notice how lovingly she cradles his uniform when she goes to wash it, or the way her hand lingers on his body when she touches him. Then notice how Ethan dotes over meeting Debbie for the first time. In interviews, Wayne confirmed what viewers suspected: Martha is in love with Ethan, and Debbie isn’t Ethan’s niece. Debbie is Ethan’s daughter. Martha recognized Ethan’s brutality, so she couldn’t marry him. She married his brother instead. Martha and Ethan’s affair continued, however, resulting in the birth of Debbie. It’s no wonder, then, that Ethan gives his war medal to Debbie as soon as he meets her. It’s also not surprising that when Scar kidnaps Debbie and takes the medal as his own, Ethan takes it as a personal slight.

By imbuing The Searchers with this covert subplot and progressiveness, Ford drives home his point about women being the most intelligent, perceptive characters in both the film and — by extension — the Western as a whole. He also underlines Ethan’s dehumanization: he’d rather murder his own daughter than accept her after living with Native Americans. Ethan’s war medal comes to symbolize how he selfishly feels that the Comanche stole his honor. Ethan doesn’t search for his abducted daughter out of love; he does so out of pride. Wayne plays Ethan’s layers with steely resolve and unyielding bitterness. In The Searchers, he gives the performance of his career.

The Searchers Strikes the Perfect Balance Between Light & Dark

The Movie is a Masterclass in Filmmaking and Cinematic Storytelling

All this discussion of murder, racism, dehumanization, and violence makes The Searchers sound more dour than it actually plays on screen. Despite the movie’s darkness and grave themes, Ford has the intelligence to pepper in some wild action to keep the story moving. The raid on the Edwards homestead (later copied by George Lucas in Star Wars) plays with white-knuckle suspense and thrills. Likewise, the film’s climax, in which the US Calvary battles Comanche raiders, stands on par with some of the greatest action sequences ever filmed. It’s hard to look at the Battle of Shrewsbury in Chimes at Midnight, Indiana Jones battling a tank in Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade or the battles for the Five Points in Gangs of New York and not notice the parallels. Indeed, Orson Welles, Steven Spielberg, Martin Scorsese, and a litany of other directors have all cited Ford and The Searchers as a major influence, and it’s hard not to see why.

Ford also knows when to throw in some good humor. For all its seriousness, The Searchers also has some very big laughs. Consider a wedding party that devolves into a massive fistfight. What begins as a quarrel between two men quickly devolves into a full-on brawl, with men in their fanciest suits clawing and biting at each other in the dust. Ethan forbids the women from coming outside to watch, so instead, the ladies all crowd in windows, cheering and laughing as the fight intensifies. The scene feels like it could fit alongside anything in Duck Soup, the Marx Bros. comedy. Later on, a brief scene following the climactic battle between the Calvary and the Comanche also features Ward Bond’s Rev. Clayton bent over, his bare bottom exposed as a medic pours whiskey over Clayton’s posterior. The medic then explains that Clayton didn’t sustain the wound in battle. Ford clearly means to imply that all that riding on horseback inflamed Clayton’s hemorrhoids, which makes his situation all the more hilarious. The good-ole-boy humor of The Searchers keeps it from ever feeling too morose, despite its subject matter.

Ford, working with cinematographer Winton C. Hoch, also makes The Searchers a wonder to behold. Filmed in VistaVision Technicolor, the movie cries out for audiences to see it in a cinema on the biggest screen possible. Filmed in Utah’s Monument Valley (a favorite location of Ford’s), the movie captures breathtaking visuals, such as when Debbie comes running to Ethan and Marty over a sand dune. On a TV screen — even a big one — Debbie looks like a dot atop the hill. On a big screen, audiences can see more detail, and appreciate the vastness of the shot. The same goes for gobsmacking shots of a herd of buffalo grazing over a snow-covered field. The photography of The Searchers has a certain lushness to its color: its rust-colored reds, its bright greens and dusty browns. Audiences can see the dust in the air on the lens. This approach makes the film beautiful to look at, but also lends it a certain realism. The epics of today, filmed on green screen soundstages or with giant LED screen backdrops, could never look so authentic.

The Searchers is the Greatest Anti-Western Ever Made

The Movie is a True Genre Classic and a Timeless Cinematic Masterpiece

In The Searchers, Ford shows off both his skill as a master craftsman and the potential for a film to show epic splendor. But for all its technical strengths, the story (both textual and intimated) remains The Searchers’ greatest asset. The aforementioned closing shot mirrors Ford’s opening: the camera pans from inside a shadowy house out into the expanse of the Old West, with Ethan returning home. In that moment, Ethan has the potential for the domestic bliss that had eluded him during the war years. But pride inflames his hatred with the kidnapping of his daughter. He rebuffs Marty’s pleas for love and humanity. He sets out for vengeance, not to rescue Debbie, but to avenge his pride. Even if he embraced his daughter rather than kill her in the end, one act of goodness cannot redeem a life of hate and violence. Debbie and Marty return home to heavenly domestic bliss. Ethan never can, as he’s condemned to the hellscape of the Old West forever. Worse, this living nightmare was one of his own making.

Wayne and Ford know as much, and trust the audience to understand as well. The Searchers doesn’t spell out its values, instead letting its viewers read it on multiple levels, driving home its points beyond the constraints of superficiality. In The Searchers, Ford and Wayne deconstruct and demystify the genre they helped make iconic. Can a movie that subverts type also be the best example of it? Here, it can. The Searchers isn’t just the greatest Western ever to hit screens. It’s one of the greatest movies ever made.