In typical John Ford fashion, the most profoundly poetic line from the director’s renowned masterpiece, The Searchers, is simple, if not innocuous. When John Wayne, playing a recently returned Civil War veteran, delivers his repeated contemptuous line “That’ll be the day,” he underscores America’s hostile race relations and the emptiness of man. Ford, a master of picaresque Western films with gruff protagonists with a repressed sensitivity, reached his apex with The Searchers, his 1956 sprawling adventure epic that likely inspired your favorite filmmakers working today. “That’ll be the day,” uttered by a vengeful drifter deadset on taking out his pent-up rage on local Native Americans, is a phrase imbued with skepticism. He doesn’t see the day when he’ll make peace with them, nor will he ever be satisfied in his quest for revenge. Westerns tend to dream of a “day” when America was a land of hope and nobility, but Ford’s film shows that we’re forever cursed with the sins of history.

John Ford Upends the Typical Western Hero Story in ‘The Searchers’

Of their 14 collaborations, the culmination of the vision of John Ford and the prowess of John Wayne was in The Searchers, often recognized as the finest Western in history. Their previous films, including Stagecoach, She Wore a Yellow Ribbon, and The Quiet Man, were bracing touchstones of American (or Irish in The Quiet Man) culture and wistful portraits of archetypal heroes with the weight of history on their shoulders. With The Searchers, Ford channeled American culture and history into one complex, layered, and wounded man in Ethan Edwards (Wayne). The film follows a years-long odyssey across the New Frontier by Ethan to rescue his niece, Debbie (Lana Wood/Natalie Wood), who was abducted by a Comanche tribe as a child. Accompanying Ethan is Debbie’s adopted brother, Martin Pawley (Jeffrey Hunter), who hopes to rebuild his shattered family following the Comanche raid. Ethan, however, may be lost for good.

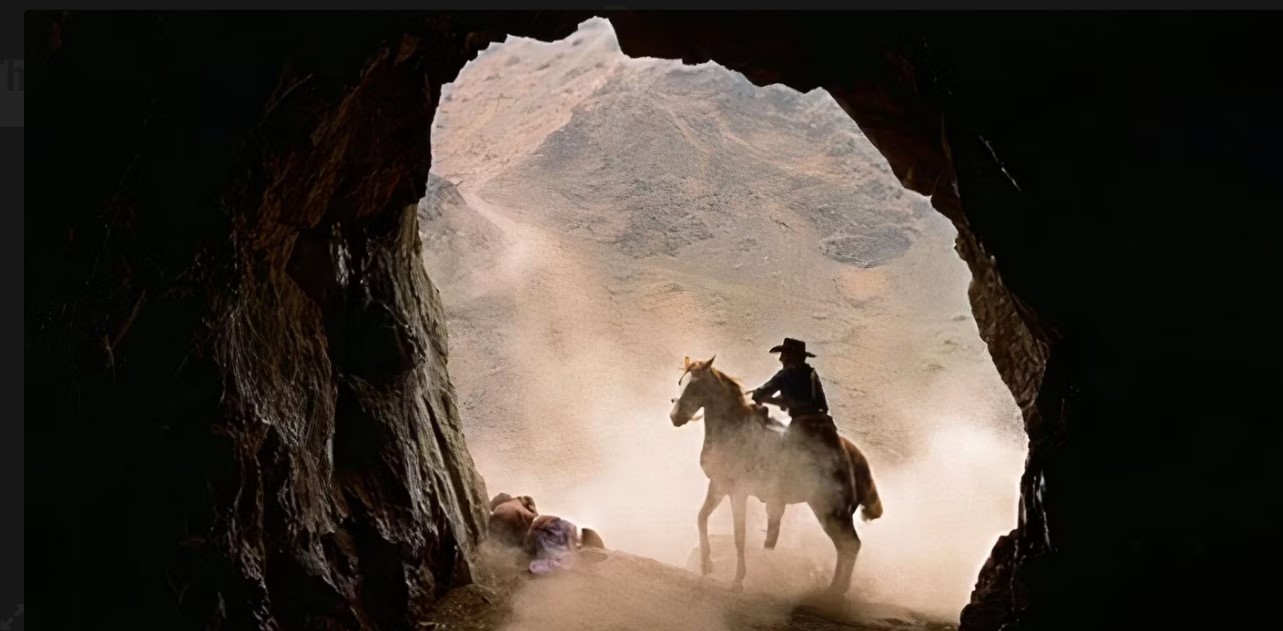

Of all its extraordinary accomplishments and artistic feats, The Searchers is a masterclass in Trojan horse storytelling. Shot in immaculate Vistavision, making each image feel like a fine painting, the film is one of the most beautiful creations put on celluloid. The depth of field and vibrant colors make even the most attention-deficit viewers immersed in each exterior scene shot in Ford’s beloved Monument Valley in Arizona. The film, despite its dealings with thorny social politics, has the structure of a familiar, crowd-pleasing adventure saga, where we follow our mighty hero through the open field and encounter various friends and assailants. Intercutting with the journey is the domestic life of Martin’s lover, Laurie (Vera Miles), praying to see the day Debbie is rescued as she reads hopeful letters sent by Martin juxtaposed with Ethan’s cutthroat means of finding the Comanche tribe.

There Is a True Dark Side Beneath the Surface in ‘The Searchers’

This picturesque story is rounded out by the last remaining vestige of Americana, hoping that their valiant heroes, Ethan and Martin, salvage the Jorgensen name, but there is something far more rotten and concerning at the heart of The Searchers. From the outset of the film, before Debbie’s kidnapping, Ethan, through Ford’s superb blocking and framing, is shown to be aloof — distant from the Jorgensen family, with his cold disposition stemming from his war trauma. He fawns over Debbie’s childish innocence, but he hardly knows anything about her internally. After the raid and abduction, while the rest of the family is straightforward in their determination to rescue her, Ethan views the precious girl as a lost cause, a former beacon of hope now tainted by her assimilation into Comanche life. Ford officially upends any notion of his film being a wholesome heroic fable in the scene when the grown-up Debbie runs to embrace Martin. Ethan, distant from the action, looks to kill Debbie, wearing Comanche attire and speaking in their Native language, but Martin blocks his line of fire.

For Ethan, the quest for Debbie’s whereabouts wasn’t a rescue — it was an assassination. The Searchers is an exercise in pulling the rug out from under the audience. Ford lulls the viewer into a sense of protection, providing them with an emotionally vibrant hero’s journey with a sweeping orchestral score and a healthy dose of humor. As the story progresses, Ford completes this Trojan horse act by unveiling the deep-seated bigotry fueling Ethan’s mission. The burning passion conveyed in Ford’s glossy visual language is matched by Ethan’s searing rage, whose Civil War experience made him desensitized to violence and bloodshed and inflamed his racism towards Native Americans. Ford deconstructs the nuclear family dynamic by indicating that Ethan is more or less indifferent to Debbie and the Jorgensen family, and the girl’s abduction is merely an excuse for him to embark on a rampage against the Comanche tribe.

America’s Prevailing Bigotry Is Captured by John Wayne in ‘The Searchers’

The Civil War was declared as a last-means effort to unite the nation once and for all, but Ethan represents that the most stubborn streaks of bigotry are unsalvagable. The film opens and ends with Ford’s iconic doorframe shot of a gorgeous open vista with the desert’s boulders brushing up against the horizon, and walking in the frame all by his lonesome is Ethan. His bigotry defines his character, and when the mission is “accomplished,” he is a lonely drifter without a purpose. Although combat has ceased fire, The Searchers presents a sobering reality of America with a prevailing undercurrent of hostile race relations. The war-battered Ethan refers to Native Americans with such casual disdain that it evokes a banality of racism in this world. This sentiment of coded and implicit bigotry has unfortunately made The Searchers feel evergreen.

Ethan Edwards is not the only character to normalize the vilification of Native Americans in the film, which may cause modern audiences to decry The Searchers as “problematic.” However, Ford’s unflinching portrait of racism circulating the Jorgensen family, who displays just as much Comanche fear-mongering as Ethan, is wholly honest and confrontational, and the director trusts that viewers can separate depiction from intent. While Ford was not always progressive with his treatment of non-white characters, he offered plenty of sympathy for Indigenous people in The Searchers that most Westerns were blind to. In one encounter with a Comanche woman, Martin, in a communication error, inadvertently weds her through a transaction. Ethan ridicules both parties, and we’re led to believe Ford is too, but later, in a scene highlighting the sheer horror of America’s long history of violence against Native Americans, we see that woman slain by a group of soldiers. In the film, the line between mocking Native rituals and customs and mass genocide is alarmingly thin.

Although his expansive filmography tracks the history of America, John Ford’s economy of gestures and minimalist poetry is why he remains a canonical artist and signature voice of this nation. The Searchers, the finest hour for both Ford and John Wayne, is a concise point-A to-point-B narrative wrapped with an epic’s worth of pathos and the disillusionment of nobility. From the way people glance at each other to specific body language within a space, the film sears into one’s mind due to its simple gestures. Ford preferred to keep the skyline horizons away from the middle of the frame, as his characters and portraits of America were always oblique.

The Searchers is available to rent on Prime Video in the U.S