Given their long and illustrious careers in acting and filmmaking, it’s no surprise that both John Wayne and Henry Fonda starred in quite a number of World War II films. These films vary in quality, with some being great and the others falling short in different ways. That said, it goes without saying that the biggest and best World War II film that Wayne and Ford starred in was The Longest Day.

Based on countless first-person accounts of Operation Overlord (better known as D-Day) that occurred on June 6, 1944, The Longest Day showed how the Allied Forces stormed the beaches of Normandy and brought the fight to Nazi Germany. Wayne and Ford played prominent characters and real-life soldiers in the film, but believe it or not, they weren’t even the main attraction.

John Wayne & Henry Fonda Were Two of The Longest Day’s Most Important Characters

The Film Cast the Actors as Real-Life Heroes From D-Day

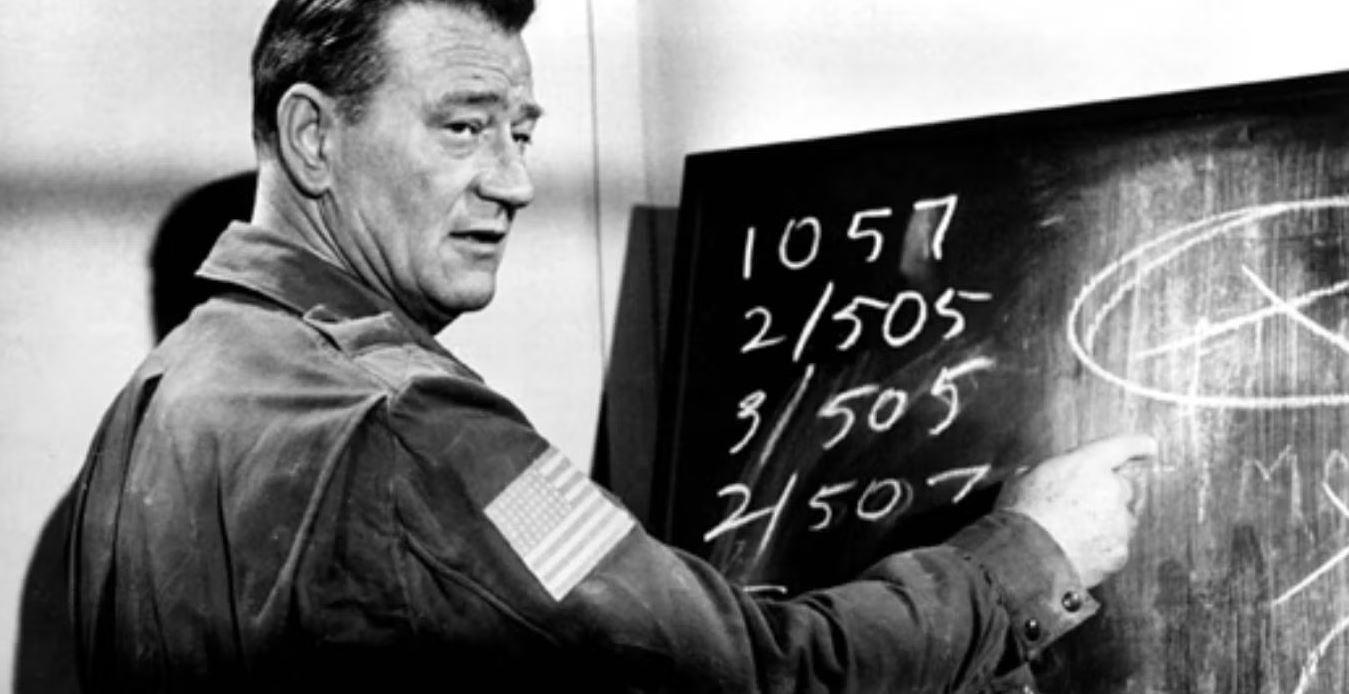

The Longest Day strove to be as historically accurate as possible, and it achieved this through its characters. Both the officers and the soldiers’ portrayals were based on real accounts. Wayne portrayed Lieutenant Colonel Benjamin H. Vandervoort: one of the paratroopers’ main commanding officers during the airborne landings in Normandy. Vandervoort became a wartime legend when he commanded the defense of the town of Sainte-Mère-Église despite breaking his ankle when he landed. The only real discrepancy between Wayne and Vandervoort was that the actor was 55-years-old at the time of filming, while the soldier was just 27 when he landed in France. Meanwhile, Fonda took on Brigadier General Theodore Roosevelt Jr.: the son of Pres. Theodore Roosevelt who led the taking of Utah Beach at the age of 55. Unlike Wayne, Fonda fit his character’s age perfectly.

Unfortunately, Wayne and Fonda didn’t have a single scene together. As if that wasn’t bad enough, Wayne didn’t even get to defend the town. His time in The Longest Day ended just as he and his unit marched to Sainte-Mère-Église. Wayne spent most of his time discussing strategies, barking orders and complaining about his broken ankle instead of fighting. Needless to say, the film’s version of Vadervoort was a flat character. In contrast, Fonda got one of The Longest Day’s only substantial character arcs, but it was resolved as soon as it began. Roosevelt Jr. demanded to go to Utah Beach with his unit, and he was begrudgingly allowed to do so after a quick argument. For what it’s worth, Fonda got to close out the film by smoking a cigar and riding off into the metaphorical sunset. However, neither of these giants of Hollywood’s golden age could even be considered to be the main character.

Wayne and Fonda were just two of more than 40 big-named actors from America, Britain, France and Germany to star in the film. At best, they were side characters in an already massive gathering of side characters. There were so many characters that, at best, Wayne and Fonda only got around 10 to 15 minutes’ worth of screen time in the film’s nearly three-hour-long runtime. That being said, these two actors’ lack of a shared scene is more of a missed opportunity than a detrimental flaw. After all, The Longest Day wasn’t the kind of war film whose entire fate rested on a single actor’s shoulders. Rather, it was the biggest World War II reenactment ever put on film. Part of its spectacle came from seeing one of the biggest ensemble casts ever assembled reenact the largest military invasion in history, and the film delivered in this regard.

The Longest Day Is One of the Most Detailed World War II Films Ever Made

The Film Is Both Informative and Entertaining

The Longest Day was more of a reenactment of D-Day rather than a conventional war film. Despite its epic scale, the film had more in common with an academic documentary than it did with the kinds of adventurous World War II films that were popular during the ’60s. Its priority was to recreate as many perspectives of D-Day as accurately as possible for the big screen, not filter the invasion through a few characters’ eyes. With this end goal in mind, both the commanders and soldiers have equal shares of the spotlight. Similarly, the Allies and Nazis’ perspectives were shown as evenly as possible. Most notably, the film went out of its way to explain the operations’ logistics and orders in painstaking detail.

Besides how it cemented Nazi Germany’s downfall in a single day, what made D-Day such a historical moment was that it was one of the biggest logistical feats ever pulled off in human history. Everything and everyone had to be meticulously accounted for, especially the weather and time. One wrong move wouldn’t just endanger the lives of thousands of soldiers, but risk the Allied Forces’ entire existence as well. But as important and integral as this level of planning and scrutiny was in reality, it doesn’t exactly make for entertaining cinema. This is what made The Longest Day such a great World War II film. Not only did the film compress all this information into a tight first act, but it also made all this exposition gripping and tense. Few World War II films really bother with anything that doesn’t occur on the battlefield, but The Longest Day was the exception.

None of this is to say that The Longest Day was a dry and academic film. On the contrary, it was the biggest and most bombastic war epic of its kind, and it doesn’t disappoint even after more than 60 years. The film’s expository first hour is followed by two hours of the biggest war setpieces ever seen in the war genre. From the airborne attacks to the sea invasion, The Longest Day’s recreation of D-Day is impressive beyond words. The mere image of countless ships sailing towards Normandy or entire armies charging on the beach is more than worth the price of admission. The fact that all this was done at a time long before digital effects were even conceptualized is a testament to the seemingly lost art of practical filmmaking. What the film lacks in character and narrative, it more than makes up for with spectacle and entertainment.

The worst that could be said about The Longest Day was that it romanticized World War II in that quaint way that only classical Hollywood films can get away with. The most obvious instance of this was the complete lack of gore in what’s historically been proven to be one of World War II’s bloodiest battles. Additionally, all the characters are depicted as cleanly as possible. The Allied soldiers are flawless heroes, while the Nazis are professionally apolitical soldiers. The era’s prejudices and politics — most egregiously, Nazism’s inhumanity — were never acknowledged or even mentioned. In brief, The Longest Day boiled World War II down to an easy battle between the good guys and the bad guys. To say that these don’t reflect history and present reality would be an understatement.

The Longest Day Is a Bygone Kind of Cinematic Epic

The Film’s Size and Scale Remain Unmatched

In some ways, The Longest Day is one of the last films of its kind. World War II epics were literally the biggest films of the ’50s and the ’60s, but few, if any, could match even a fraction of The Longest Day’s sheer scale. Of the countless World War II films released in the next 10 years, only Battle of Britain, A Bridge Too Far and Tora! Tora! Tora! came close to matching its epic presentation. But even with their equally massive casts and production values, they still fell short by virtue of the battles they adapted paling in comparison to just how titanic an invasion D-Day was. In fact, D-Day was such an unfathomably enormous undertaking that the film had to cut out entire battles just so that it could fit an acceptable runtime.

It wouldn’t be until the 2000s that World War II epics made a brief comeback through Saving Private Ryan and Dunkirk. Yet even with the benefits of modern technology, they still couldn’t escape The Longest Day’s shadow. Saving Private Ryan’s opening assault on Omaha Beach is legendary in its own right, but it’s only the prelude to a small squad’s trek through France. From there, the battles shrank in scale but never in intensity. Similarly, Dunkirk’s armada of civilian vessels and stranded soldiers are a sight to behold, but they’re still nothing to seeing paratroopers and infantry storm multiple positions in the same film.

The Longest Day is the kind of film that isn’t made now, and it’s not difficult to see why. It was just so impossibly big that, then and now, filmmakers and studios understandably didn’t even bother trying to beat or match it after its release. Not helping was that, by the ’70s, the World War II genre was on its way out. With each passing decade, there was less incentive to make another war epic this ambitious. There was and probably never will be another World War II epic like The Longest Day, but that’s alright. It’s more than enough that a film this singularly massive simply exists, and is watched and appreciated by more generations of moviegoers.