For decades, John Wayne, best known for True Grit, The Searchers, and Stagecoach, wowed audiences everywhere as a Western star. To this day, there isn’t a name more associated with the genre than Wayne’s, and his legacy has remained a strong staple well into the 21st century. But back in 1960, the Duke put it all on the line when he made The Alamo, a historical war picture that took a deeper look at the infamous “Battle of the Alamo,” a conflict between Texas and Mexico in 1836. But this motion picture nearly bankrupted the Western legend, who also directed and produced the film, leaving an interesting legacy behind of its own as a result.

‘The Alamo’ Was a Passion Project for John Wayne

There’s no doubt that John Wayne was a man of passion, and often played similar Western heroes on screen in an effort to build the myth of John Wayne that has continued to exist in Hollywood long after his death in 1979. But about twenty years before he passed, the Duke worked hard to bring the story of the Alamo to the big screen. According to historians Randy Roberts and James S. Olson in their book, A Line in the Sand: The Alamo in Blood and Memory, Wayne began development on The Alamo back in the late 1940s, and was working with Republic Pictures on the film until the studio axed the project due to budget concerns (Wayne wanted $3 million to make the movie). That script eventually became The Last Command, and was made without Wayne’s involvement. Soon after, the Duke established Batjac Productions alongside producer Robert Fellows, which would be the production house he’d use to see the project through.

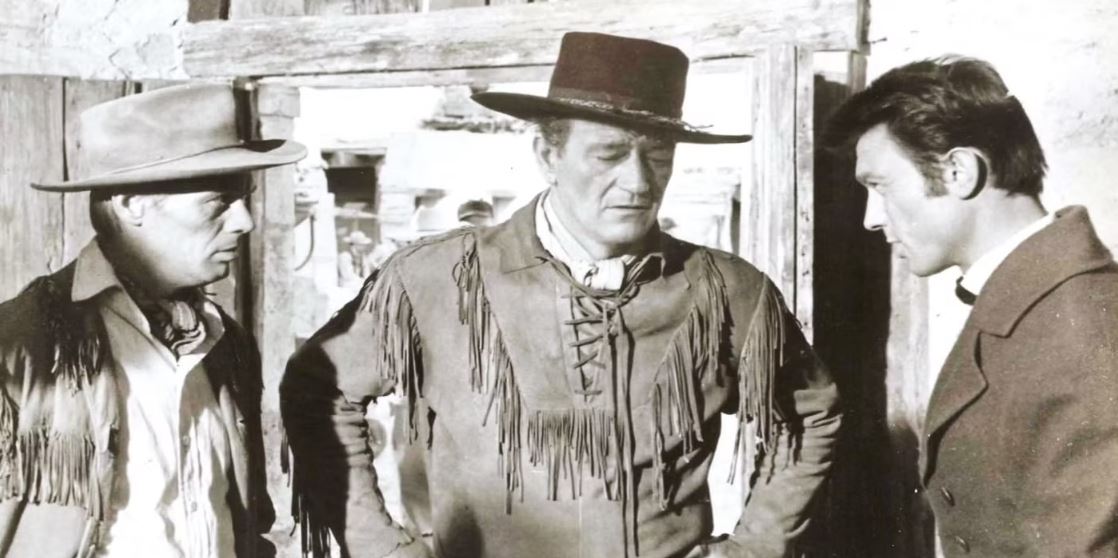

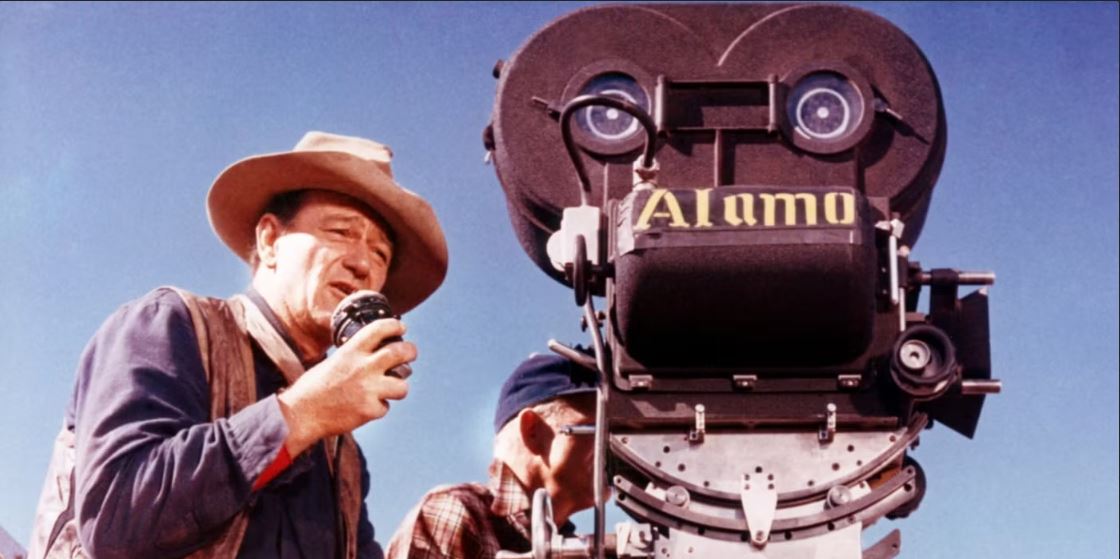

John Wayne couldn’t be kept from the Alamo forever. The Duke took some time to regroup and rework the project, and would eventually revisit it with Angel and the Badman partner James Edward Grant writing the picture. Wayne originally had no interest in starring in the picture and was solely interested in directing, but eventually, he was forced to take on the leading role of Davy Crockett when money continued to be an issue. When Wayne went looking for other financial backers to bring his enormous vision to life, he was forced to make a deal with United Arists. The studio offered the Duke a considerable $2.5 million in addition to being The Alamo’s distributor, but only if Wayne would also star. Additionally, as Roberts and Olson note, “Batjac, Wayne’s own company, would have to invest $1.5 to $2.5 million” as well. Despite the terms, Wayne accepted the deal, though that still wasn’t enough to make The Alamo… at least not on the incredible scale he was hoping for.

According to Roberts and Olson, Wayne went to Texas oilmen such as Clint W. Muchison and brothers I.J. and O.J. McCullough for more funding, eventually convincing the businessmen to invest in the film about their rich history. Their only stipulation was that it be shot in Texas, which the Duke agreed. Years later, the Western icon revealed that he was forced to use his own funds to continue making the picture, putting about $1.5 million into the film after taking out second mortgages and putting up his own vehicles for collateral. But why did he do such a thing? Well, he saw Davy Crockett and the other men who died at the Alamo as heroes, and for years he fought to honor them the only way he knew how: by making a movie about them.

John Wayne Wasn’t Concerned With ‘The Alamo’s Budget

“What kind of men were they? Well, we know that they died and that they were heroes, but nobody wants to die and nobody just decided to be a hero. It has to be forced on you, and that’s what happened to them,” Wayne explained when promoting the film, which was released in October 1960. But more than that, the Duke had become obsessed with the story, which many believe may have been something of a midlife crisis for the actor, who had skirted the draft during World War II to continue making Westerns in Hollywood. “I think making The Alamo became my father’s own form of combat,” Wayne’s daughter Aissa later hypothesized in A Line in the Sand. “More than an obsession, it was the most intensely personal project in his career.”

While The Alamo didn’t do exceptionally well either critically or at the box office, it was still Wayne’s first official directing credit (he went uncredited for his work on 1955’s Blood Alley). “It’s costly, and that’s the only question they ask me, Tim, is how much did it cost?” Wayne told ITN’s Tim Brinton in 1960 following the premiere. “And I think that is unimportant. We spent as much money as it would take to make this picture in the best manner it could be made. I wish that every picture could have that opportunity, but there are a lot of subjects that can be made that wouldn’t cost this kind of money.” For Wayne, The Alamo wasn’t something he was willing to give up on. It took the Duke over a decade to get the movie made, and he eventually succeeded in bringing the tale to life. It was nominated for seven Academy Awards, and took home the Oscar for Best Sound in 1961.

Decades later, The Alamo would be remade in 2004 with Billy Bob Thornton and Patrick Wilson in the leading roles. The film was a box-office bomb and, despite its concern about the history of the Alamo (something Wayne’s film played fast-and-loose with), it wasn’t quite the exciting war drama that the Duke’s original was. Not only that, but it’s soulless attitude toward the material paled in comparison to Wayne’s genuine passion for the project. No, Wayne’s Alamo wasn’t exactly the most historically accurate, but the Duke had given it his all, and that shone through despite its flaws.

Footage from ‘The Alamo’ Was Used in ‘How the West Was Won’

Of course, the legacy of The Alamo doesn’t just end with the 2004 remake. Footage from the production of The Alamo would later be repurposed into John Ford’s segment of the Western epic How the West Was Won, which featured John Wayne as General William Sherman. While the timeline between The Alamo and How the West Was Won is off (the former took place in 1836 while the events of the latter take place during the American Civil War), Wayne allowed Ford to use shots from The Alamo, particularly of Mexican soldiers marching on. “The film did, however, include a shot of Santa Ana’s massed army advancing on the Alamo, taken from The Alamo,” noted pop culture historian Sir Christopher Frayling in his introduction to How the West Was Won, as evident in Cinema Retro Magazine. “Which may well have involved one of Ford’s contributions to the second unit on that film.”

Following the mixed reception to The Alamo, Wayne continued to make pictures that proved his worth as an actor and a filmmaker. He went on to make The Comancheros, The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance, Big Jake, The Cowboys, True Grit, and eventually his final picture, The Shootist. He received no credit for his directorial work on The Comancheros or Big Jake, though he is the credited director of The Green Berets, a less well-known project than The Alamo. Many believe that, due to the large sums he invested in The Alamo, Wayne continued making so many Westerns into the 1960s and 1970s because he was in financial need, but whether that’s true or not, the Duke was always one of the hardest working actors in Hollywood. Be it near the beginning of his career with movies like Stagecoach or at the tail end with pictures like Rooster Cogburn, John Wayne always worked hard to bring his characters to life, but perhaps he never worked as hard as he did with The Alamo.