If there’s anything that Quentin Tarantino is better at than making movies, it would be recommending movies. An author of film criticism and podcast host on hidden gems from his youth, Tarantino has become the preeminent celebrity voice for cinephilia. When he sings the praises of a classic or contemporary film, it’s the highest honor out there. Tarantino is so outspoken and passionate about his favorite movies and directors that a whole library of films could be centered around his taste. Avid followers of Tarantino know his idols at the top of their heads, and no director influenced the late 20th century’s most impactful filmmaker more than Howard Hawks. One Hawks film, Rio Bravo, laid the groundwork for Tarantino’s impeccable filmography and distinct taste for the art form.

Howard Hawks Was an Auteur Across Genres Within the Studio System

On the outside, a rebellious spirit in Quentin Tarantino, who has consistently marched to the beat of his own drum and broke all the rules of mainstream cinema, would have no kinship with a career studio journeyman like Howard Hawks. While Hawks did work within the studio system and never aimed for “high art,” he was undoubtedly an auteur like his contemporaries, including John Ford and Alfred Hitchcock. He was a master chameleon who made bonafide classics across various genres: screwball comedies, noirs, and Westerns. Tarantino always sought to check off essential genres in his filmography, putting his unique spin on the blaxploitation (Jackie Brown), kung-fu (Kill Bill), and spaghetti Western (Django Unchained) genres. More than being a jack-of-all-trades filmmaker, Hawks represented cinema at its brightest by portraying deeply felt characters that left a seismic personal impact on a young Tarantino.

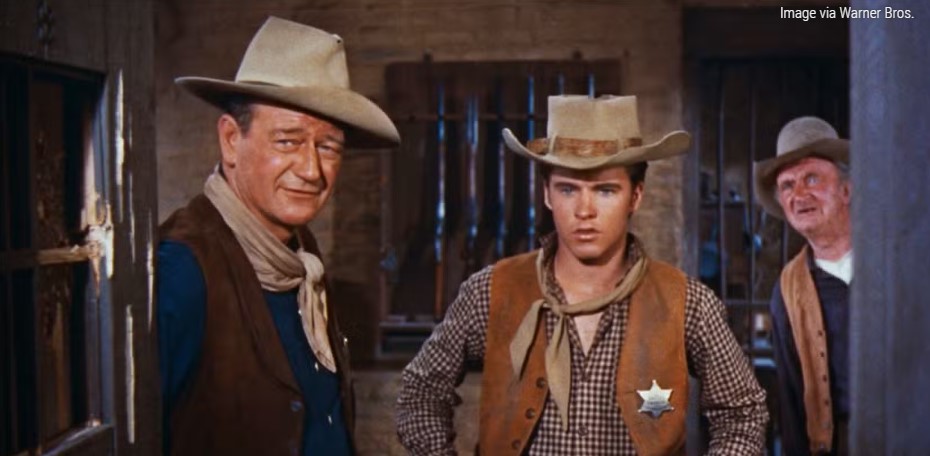

Rio Bravo, a 1959 Western starring John Wayne, is a certified classic. While John Ford and Anthony Mann popularized the Old West, Hawks was quite the genre visionary, directing other classics such as Red River and El Dorado. The film follows a small-town sheriff in the American West who enlists the help of a band of gunfighters to fend off an outlaw marching into town to break his brother out of jail. Where Ford’s Westerns were expansive, poetic meditations on American history, Hawks’ Westerns were streamlined to focus on character, taking on the sentiment of a “hangout movie,” where you learn to bond with the people on screen. In an interview with Charlie Rose, Tarantino championed Hawks as the “single greatest storyteller.” His knack for individual scene construction and seamless pacing made him a true master of the form without the pretense of painterly beauty that may turn off audiences from Ford.

Hawks once stated that a good movie is “three great scenes and no bad scenes.” By focusing on rich characterization rather than intense plotting, Hawks established himself as a sheer entertainer, first and foremost. This is a shorthand way of describing the dynamic nature of his films, which often lack a rigid central plot or straightforward narrative. Bringing Up Baby, his seminal screwball comedy featuring Katharine Hepburn and Cary Grant, moves at a relentless pace, breezing past one set piece for another. The Humphrey Bogart-Lauren Bacall noir, The Big Sleep, has a notoriously opaque mystery, but it doesn’t matter when each scene contains riveting detective work by Bogie’s Philip Marlowe. Tarantino’s films follow a Hawksian vignette structure, often divided between chapter breaks. He follows Hawks’ advice as well as anyone, with most of his films being a series of great scenes.

Quentin Tarantino Has a Personal Connection to Howard Hawks’ ‘Rio Bravo’

Tarantino has never been shy to honor the work of Howard Hawks in the press, but his appearance at the 2007 Cannes Film Festival is perhaps the most emotionally transparent the director has ever been in public. Speaking to the crowd at a private screening for Rio Bravo, he raved about what makes the film so great, calling it one of the great “hangout movies.” “There are certain movies that you hang out with the characters so much that they actually become your friends,” he said, further noting that this quality rewards repeat viewings, as you only grow more accustomed to the characters, Sheriff Chance (Wayne), Dude (Dean Martin), Colorado Ryan (Ricky Nelson), and Feathers (Angie Dickinson).

Rio Bravo spoke to the young movie buff who looked to the screen for leadership. Growing up without a father, Tarantino latched on to Hawks’ ideas about masculine principles. He admired that his construction of a strong man wasn’t based on the class system or propriety, but rather, “what is expected of a man,” through behavior alone. For better or worse, he adopted the ideas on the screen as an avatar for who his role model should be. Understandably, given the personal kinship, Tarantino confirms that, at one point, Rio Bravo was his all-time favorite film.

How Has the John Wayne Western Influenced Quentin Tarantino’s Movies?

With other Tarantino influences, such as Sergio Leone films or Elmore Leonard novels, the influences are palpable on the screen. With Howard Hawks, you might have to work harder to connect the two, but Tarantino has consistently invoked the hangout vibes of the Rio Bravo director. Since his debut film, Reservoir Dogs, sharp dialogue has been his defining trait, particularly in mundane conversations about Madonna songs or McDonald’s in France. These exchanges between violent gangsters, disconnected from the central storyline, provide Tarantino’s films with warmth and rich nuance. By repeatedly watching Rio Bravo, Tarantino learned that character growth can manifest from intimate conversations between characters who share the same passions as the average viewer.

Compared to most classic Hollywood films, Hawks’ characters mirrored the behavior of everyday people, and Tarantino took it one step further by mimicking the frivolous, but passionate, conversations you’d have with a close friend.

When making Jackie Brown, Tarantino wanted to evoke “the way that I always felt about Rio Bravo, which is a movie that I can watch every couple of years. It’s just like, ‘I know those people now.'” His follow-up to Pulp Fiction is the most plotless Tarantino joint, as it ultimately focuses on character redemption and yearning for a more satisfactory life. It’s a film about the music people listen to, and the unique relationships between the ensemble cast of characters. Tarantino’s most recent film, Once Upon a Time… in Hollywood, returned to a Hawksian hangout vibe, this time in the form of a love letter to the last days of innocence. Upon first viewing, the relaxed, easy-going tone of the film was disarming, but, as Tarantino cites with Rio Bravo, it rewards repeat viewings. With enough time, you could watch Cliff Booth (Brad Pitt) drive around Hollywood Boulevard all day. It’s no surprise that Tarantino’s two most sympathetic films, Jackie Brown and Hollywood, are the ones that aren’t concerned about revenge or disastrous crimes gone wrong.

Jackie Brown’s titular protagonist, played by the Queen of Blaxploitation,Pam Grier, is Tarantino’s homage to the Hawksian woman, an archetype of strong-willed, fast-talking, independent female characters in Hawks films. Like the Hawks characters played by Hepburn, Bacall, and Dickinson, Jackie seeks to control her own destiny in the face of prosecution, betrayal from her criminal employer, and the lingering perils of aging. In Hollywood, Rick Dalton (Leonardo DiCaprio) and Cliff Booth may be past their primes in the rapidly altering movie landscape, but they live by an unwavering code. They refuse to acquiesce to the new wave, not out of sheer stubbornness, but out of reverence for the past. Similar to how a young Tarantino, lacking a father figure, latched on to the sheriffs in Rio Bravo, the adult Tarantino clearly admires Rick and Cliff as two forgotten gems of old Hollywood. We sense in his writing that he hopes to carry the same level of dignity toward the end of his career as Hollywood continues to change.

Quentin Tarantino Wants To Go Out on Top

If Howard Hawks inspired Quentin Tarantino to become a filmmaker, he, ironically, also taught him to step away from the director’s chair. Tarantino’s self-imposed 10-movie rule, where he promises to quit directing feature films after completing his 10th, is a cautionary measure on his part, as he firmly believes that directors, even the best ones, lose their fastball in their later years.

Tarantino, who recently scrapped his film about a movie critic in the 1970s, has already proven to be finicky about his swan song film. Amassing an immaculate filmography with no holes is sacred to him, and making his equivalent of the middling Rio Lobo, Hawks’ last film, would stain his body of work. He has also invoked Cheyenne Autumn and Buddy Buddy, lesser, late-period films by John Ford and Billy Wilder, as justification to go out on top. From his childhood through his career, Howard Hawks lingers over Tarantino’s work more than any other figure.