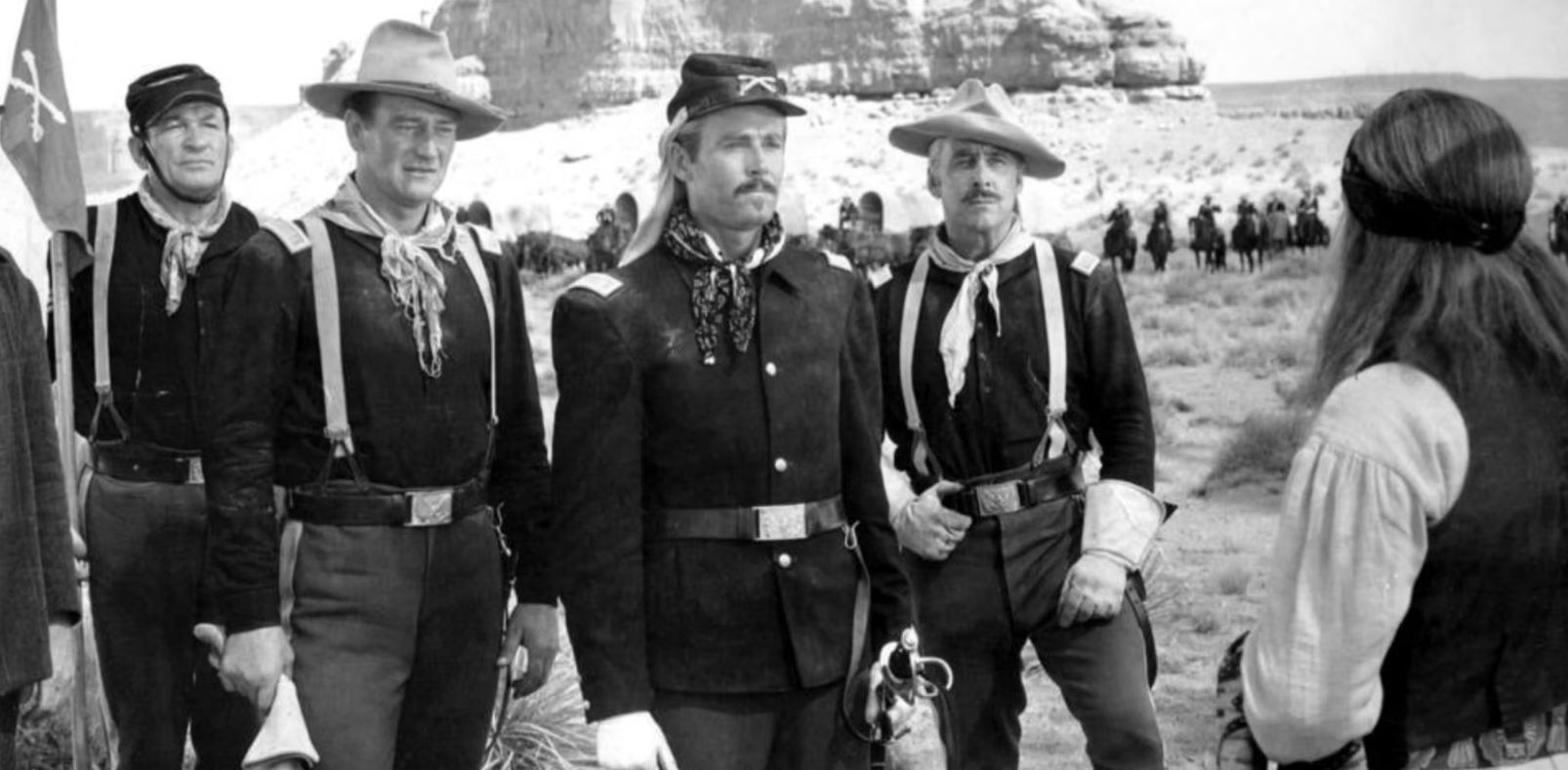

Fort Apache is a 1948 Western made by John Ford starring John Wayne and Henry Fonda. The film is the first of a trilogy (with 1949’s She Wore a Yellow Ribbon and 1950’s Rio Grande) by Ford dealing with the US Cavalry in the West after the Civil War. Ford produced Fort Apache with Merian C. Cooper (King Kong) under the banner Argosy Pictures for RKO Radio Pictures Studio. It is considered to be one of the first movies to present “a pro-Indian” view of Native Americans. Fort Apache set a trend, followed by Broken Arrow, Cheyenne Autumn, and other films that continued the trend of more accurate portrayals of Indigenous characters.

Frank S. Nugent wrote the Fort Apache screenplay from a magazine story, “Massacre,” by James Warner Bellah. The story borrows incidents from and closely traces the outline of General George Armstrong Custer’s career—West Point graduate, service as a brigadier general in the Civil War, sent west as a lieutenant colonel to command the 7th Cavalry at Fort Riley, Kansas, during the Indian Wars, Little Big Horn. Ford adds physical details to make Fonda, who, not surprisingly, almost steals the picture away from Wayne, look more like Custer.

What is ‘Fort Apache’ About?

Widower, Former Civil War General, now Lieutenant Colonel, Owen Thursday (Fonda) arrives with his daughter Philly (Shirley Temple) to take command of an isolated Fort Apache during the Indian Wars. At the same time, 2nd Lieutenant Michael O’Rouke (John Agar, Temple’s husband at the time) shows up. The recent West Point graduate shows an immediate romantic interest in Philly (and vice versa). Meanwhile, Thursday can only stew in anger over the perceived insult of his new wilderness assignment and demotion in rank.

At Fort Riley, Thursday takes over from the popular previous commander, Captain Kirby York (Wayne), much to the chagrin of the men at the fort, including O’Rouke’s Sergeant Mayor father (Ward Bond), who acts as a fatherly buffer between the rigid new commander and the men who are unaccustomed to such high-handedness. After a murderous attack on a small detail of cavalrymen by renegade Indians, York tries to convince Thursday that they were reacting to the mistreatment on the reservation by the corrupt government agent and proposes a meeting with the Apache leader Cochise to make peace. Thursday sees York’s proposal as a way to lure Cochise into an ambush and to make a new name for himself.

‘Fort Apache’ Presents Opposing Visions of America

Fort Apache presents two opposing views of America in the 1870s, personified by its protagonists, Thursday and York. Thursday represents the view of the East that Native Americans stand in the way of Manifest Destiny, the “preordained” Westward Expansion of white settlers. We hear Thursday, newly arrived in the West, speak of being glorified by the Eastern newspapers as he secretly contemplates the elimination of Cochise. On the other hand, York has spent more time in the West and has come to understand the native peoples as having been there first. He represents a more enlightened view that seeks to find a way to coexist fairly and peacefully with the First Nations people.

In reviewing Custer’s life, on which the film is loosely based, Kevin M. Levin concludes, “Custer’s racial outlook was perfectly consistent with the overarching racial views of white Northerners and Southerners and those he expressed publicly during Reconstruction. The United States was a white man’s nation. The very existence of the United States was predicated on the dispossession of the indigenous people. If Custer was wrong, ultimately, it was because the nation was wrong.” In different contexts, the same two opposing views—cooperation versus domination—continue to exist today.

The film also displays another conflict: the conflict between mindless duty and decency, between the spirit and the letter of the law. York believes in mutual respect for the Indians and understands that Cochise broke the treaty and left the reservation out of frustration over mistreatment by the government’s representative. He gives Cochise his word that there will be peace if he returns. His superior, Thursday, in keeping with his refusal to allow his daughter to marry beneath his social station, believes Indians are not worthy of respect and considers York’s promise a trick he can use to lure Cochise into a deadly ambush. York naturally feels betrayed and used. Thursday’s actions further represent the government’s lies, corruption, and bad faith.

Then, at the last minute before the final battle, Thursday finds a pretense, against York’s protests, to order him and young O’Rourke back out of danger, sensing that York should live to succeed him as commander of the regiment and that O’Rourke and his daughter are in love and are destined to marry. His final actions seem to attempt to atone for what he ultimately realizes to have been mistakes. Finally, when newspaper reporters ask him years later to remember Thursday’s legacy, York speaks only of his bravery, not his foolishness. York has a duty to speak the truth, but he tempers it with a larger and more charitable knowledge, unintentionally supporting the false legend of the Colonel’s glory. This tension between duty to the law and its spirit also persists today. It is one of the reasons why the film continues to be relevant.

Did ‘Fort Apache’ Really Start a Trend to Portray Native Americans Fairly?

So-called “Indians” have existed in film since the very beginning of the business. Cecil DeMille’s The Squaw Man (1913), long thought to be the very first feature film made when the East Coast studios moved to what is now Hollywood, dealt with the issue of interracial marriage between whites and Indians. In keeping with the ethnocentricity of the country’s colonial and expansionist past, the predominant image of Native Americans in the early decades of motion picture history was of bloodthirsty savages who only lived to prey on whites. This was the stuff of hundreds of serials and B movies for decades.

Before Fort Apache, some filmmakers attempted to portray Native Americans more realistically and respectfully. Films like The Vanishing American (1926) and Cimarron (1931) tried to be sympathetic and understanding even while thoughtlessly using whites to play natives. It was indeed John Ford’s 1948 epic that set the tone for a revised look at Indigenous characters, showing them as honorable but wary, dignified, naturally peaceful, reasonable, and strategically superior warriors. According to his biographer Scott Eyman, Ford had formed this view while working with the Monument Valley tribes on Stagecoach in 1939 and cultivated it with each new project or vacation to that area until the end of his life.

In his definitive guide to the Western, The Six-Gun Mystique, Western scholar John G. Cawelti documents that there was indeed a change in how Native Americans were portrayed after Fort Apache in 1948, typified by Broken Arrow (1950), Apache (1954), and Run of the Arrow (1957). Though still not entirely realistic, they dealt with Native people more complexly. Ford particularly used Indigenous peoples as actors in Cheyenne Autumn (1964). Late 20th-century films went even further toward fair and faithful portrayals with A Man Called Horse (1969), Little Big Man (1970), Dances With Wolves (1990), and Last of the Mohicans (1992). The 21st Century has witnessed the advent of films by Native filmmakers like Smoke Signals (1998), Atanarjuat: The Fast Runner (2001), and Reservation Dogs (2021), depicting their own cultures in the modern world.

Fort Apache was immediately popular, critically acclaimed, and financially successful upon its release. It has become a classic, which may account for its 100% rating on Rotten Tomatoes. Even with its flaws (attempts at comedy range unevenly from lame physical jokes to rich moments of verbal humor), it is still a well-made, exciting, and historically important work.